To Play or Not to Play

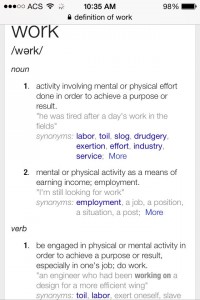

What are you doing when you’re on your XBox or Wii? What are you doing when you’re in a soccer game, or a concert, or a chess or card game? What do you call what you’re doing? Is it work? Is it play? These are all questions that David Golumbia raises in his article, Games Without Play. The concepts introduced are insightful, stimulating, and extremely thought provoking. Google’s, and society’s definitions of the words work and play are slightly different than Golumbias. Thanks to reading this article, my own ideas and interpretations of these two words is much more comprehensive than ever before. However, I have a few questions to ask now that I’ve had time to think more thoroughly on the article.

To start out his article, Golumbia retraces the roots and meanings of the word play back to France.

“Play is one of the most famous, even notorious, of concepts in contemporary literary theory, and that its reception in literary theory as well as in culture at large rests on a misunderstanding, one that hinges on both mistranslation and, in at least some cases, something like interpretive bad faith.”

As indicated in the above quote from Golumbia’s article, Games Without Play, the word play has been twisted and misconstrued throughout time and throughout our society. This is why the article comes across as slightly almost too determined, too desperate to convince and persuade the readers, and audience of Golumbia’s opinion and view.

First of all, I’d like to put out what I think I understand from this article.

“An activity entirely without rules cannot be a game.” This is stated on page 182

Another point that I’ve come away from this article is that while enjoyment is a result of play, or motivation, it is not the defining factor. This is a difficult point for me to comprehend, what is the defining factor of play then, it doesn’t seem exactly clear. Golumbia then goes on to end the first section of the article which is labeled Jeu without Jeu, by saying that it is necessary for games to have reinterpretation, and flexibility in the rules.

In my English class, which was assigned your article to read, a discussion came up where we were talking about a computer game of chess, and a human game of chess. The flexibility and unpredictability of another human being versus the programmed, inevitable actions of a computer are vastly different. You can never know for sure what exactly a person will do, what action and decision they will make. There are so many uncertainties and variables with people that it is impossible to compare it to a computer game.

I believe that Golumbia has drastically over analyzed the terms work and play. I firmly believe that there is really no reason to take these two words and transform them into more than they really are. In my opinion, the concepts of work and play are not something tangible that you can define in a cookie-cutter way. Both work and play are rewarding, you achieve something in the end, and for me, they are more of a state of mind, than anything. For example, as a violinist in the professional world of music, I can give an example to support my statement that work and play are a state of mind rather than a definable term. For the past two weeks, I’ve been hired to perform in the pit orchestra of the Fairbanks Opera Association’s production of Rumpelstiltskin. I get paid for rehearsals and concerts. I did an experiment and thought of one rehearsal as it being work. Then another rehearsal I thought of it as play. It worked both ways. Both ways were enjoyable, both ways were professional, both ways were structured, and both states of mind had an end result that had rules, and an ending conclusion that was satisfying.

Golumbia continues on in the article and gave me a few sentences that I found deeply intriguing and thought provoking. He writes that video games have a lot more to offer than entertainment and actually develop and hone work ethics in people as they play them.

On page 194, he says “I am suggesting that programs like WoW and Half-Life do not merely resemble the capitalist structures of domination, but that they directly instantiate them and, in important ways, train human beings to become part of those systems.”

Video games influence our subconscious, in however subtle ways. To quote Golumbia again from page 201, “the world presented by WoW is not precisely our world, but, in significant ways, it mimics exactly the wish that capital and globalization encode for us.” This prompts readers to rethink the way that video games affect us, what parallels to the real world are there, and how are these actions that we act out on screen affecting our actions in the real world?

Reading Golumbia’s article, Games without Play was challenging, fascinating, and, depending on the point of view approached with, could be thought of as play, and or, as work.